The hospital technology, typically used to identify human ailments, captured perhaps the world’s smallest magnetic resonance image.

As our devices get smaller and more sophisticated, so do the materials we use to make them. That means we have to get up close to engineer new materials. Really close.

Different microscopy techniques allow scientists to see the nucleotide-by-nucleotide genetic sequences in cells down to the resolution of a couple atoms as seen in an atomic force microscopy image. But scientists have taken imaging a step further, developing a new magnetic resonance imaging technique that provides unprecedented detail, right down to the individual atoms of a sample.

The technique relies on the same basic physics behind the M.R.I. scans that are done in hospitals.

When doctors want to detect tumors, measure brain function or visualize the structure of joints, they employ huge M.R.I. machines, which apply a magnetic field across the human body. This temporarily disrupts the protons spinning in the nucleus of every atom in every cell. A subsequent, brief pulse of radio-frequency energy causes the protons to spin perpendicular to the pulse. Afterward, the protons return to their normal state, releasing energy that can be measured by sensors and made into an image.

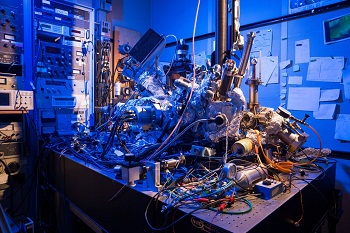

So the physicists at IBM decided to pack the power of an M.R.I. machine into the tip of another specialized instrument known as a scanning tunneling microscope to see if they could image individual atoms.

The tip of a scanning tunneling microscope is just a few atoms wide. And it moves along the surface of a sample, it picks up details about the size and conformation of molecules.

The researchers attached magnetized iron atoms to the tip, effectively combining scanning-tunneling microscope and M.R.I. technologies.

When the magnetized tip swept over a metal wafer of iron and titanium, it applied a magnetic field to the sample, disrupting the electrons (rather than the protons, as a typical M.R.I. would) within each atom. Then the researchers quickly turned a radio-frequency pulse on and off, so that the electrons would emit energy that could be visualized. The results were described Monday in the journal Nature Physics.

“It’s a really magnificent combination of imaging technologies,” said the director of the M.R.I. Core Facility at the Advanced Science Research Center in New York. “Medical M.R.I.s can do great characterization of samples, but not at this small scale.”

Lara Khouli