Scientists have identified a slew of genes that may have played a key role in the emergence of our species.

A study using a new computational method to predict motif sequences, or particular patterns in DNA relating to gene activity, has found that genes previously thought to play similar roles across many organisms are actually unique to humans.

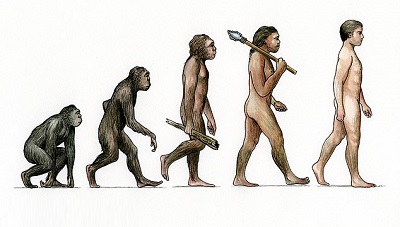

Researchers say the findings could help to explain some of the major differences between humans and chimps, our closest living relatives, by accounting for the expression of hundreds of different genes, according to Daily Mail.

In the study, researchers investigated dozens of genes that code for a class of proteins called transcription factors (TFs), which control gene activity by honing in on features known as motifs.

‘Even between closely related species there’s a non-negligible portion of TFs that are likely to bind new sequences,’ said Sam Lambert, who led the study while studying at the University of Toronto.

‘This means they are likely to have novel functions by regulating different genes, which may be important for species differences.’

The team developed a new software to search for structural similarities between the binding regions that the TFs target in the DNA, and their ability to bind to the same or different DNA motifs.

Previous studies that have attempted to this did so in a much broader way, comparing entire regions. The new research focused on just a fraction at a time for a more precise view.

And, by looking at the differences in the position of key amino acids, the team found many human TFs recognize different sequences than their counterparts in other animals.

While chimps and humans share 99 percent of their genomes, the researchers say just dozens of these TFs could lead to significant differences in gene expression.

‘We think these molecular differences could be driving some of the differences between chimps and humans,’ Lambert said.

The findings challenge earlier studies which found that almost all human and fruit fly TFs bind to the same motif sequences, the researchers note.

‘There is this idea that has persevered, which is that the TFs bind almost identical motifs between humans and fruit flies,’ said Professor Timothy Hughes, of the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research.

‘And while there are many examples where these proteins are functionally conserved, this is by no means to the extent that has been accepted.’

N.H.Kh