Enheduanna also En-hedu-Ana; (c. twenty-third century B.C.E.) was an Akkadian princess and high priestess who was perhaps the earliest known writer in history. The name En-hedu-anna, a title apparently compiled from “En” (Chief Priest or Priestess), “hedu” (Ornament) and “Ana” (of Heaven). She was the first royal daughter known to have been given the title “En” in a line that would extend for five hundred years.Identified as a daughter of King Sargon I, she was appointed high priestess of the moon god Nanna (Sîn) in his holy city of Ur. She became the most important religious figure of her day, and her evocative prayers, stories, and incantations, which were devoted to the goddess Inanna (Ishtar), were highly influential. She has been dubbed the “Shakespeare of Sumerian literature.”

Enheduanna began a long tradition of Mesopotamian princesses serving as high priestesses. Her hymns were copied by scribes for at least five centuries, and her writings are believed to have influenced the merger of the Sumerian Inanna with the Akkadian Ishtar. After her death, a hymn was devoted to her by an anonymous composer, indicating that she may even have been venerated as a deity herself.

A number of recent studies are devoted to Enheduanna. Cass Dalglish of Augsburg College, for example, recently published a new, poetic translation of Nin-me-sara, under the title Humming the Blues. It utilizes a unique approach to cuneiform translation, taking the multiple meanings of each symbol into account in order to arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of the Enheduanna’s themes and motifs.

A number of recent studies are devoted to Enheduanna. Cass Dalglish of Augsburg College, for example, recently published a new, poetic translation of Nin-me-sara, under the title Humming the Blues. It utilizes a unique approach to cuneiform translation, taking the multiple meanings of each symbol into account in order to arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of the Enheduanna’s themes and motifs.

Studies of Enheduanna were limited to Near Eastern scholars until 1976, when American anthropologist Marta Weigle attended a lecture by Cyrus H. Gordon and became aware of her. Weigle introduced Enheduanna to an audience of feminist scholars with her introductory essay to an issue of Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. Entitled “Women as Verbal Artists: Reclaiming the Sisters of Enheduanna,” it referred to her as “the first known author in world (written) literature.”

Enheduanna may have been the first feminist, or at least the first feminist we know by name. In one of her poems the goddess Inanna kills An, the former chief deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon, and thus becomes the supreme leader of the gods. It seems Enheduanna may have “promoted” a local female deity to the Queen of Heaven. Might this be considered the first feminist poem? Was Enheduanna commenting on the male-dominated society in which she lived, and perhaps even “projecting” her wishes on male rivals, to some degree?

Enheduanna has also been recognized as an early rhetorical theorist by scholars such as Roberta Binkley. Her contributions include attention to the process of (writing) invention as well as emotional, ethical and logical appeals within her poem “The Exaltation of Inanna.” Rhetorical strategies such as these establish rhetorical theory nearly 2,000 years before the classical Greek period.Binkley suggests that, while Enheduanna wrote “rhetorically complex sophisticated compositions” that predated the Ancient Greeks by millennia, however her work is less-well-known in rhetorical theory due to her gender and geographic location.

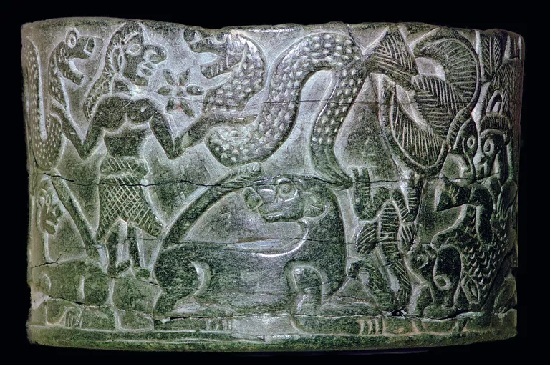

Enheduanna composed several works of literature, including two hymns to the Mesopotamian love goddess Inanna (Semitic Ishtar). She wrote the myth of Inanna and Ebih, and a collection of 42 temple hymns. Scribal traditions in the ancient world are often considered an area of male authority, but Enheduanna’s works form an important part of Mesopotamia’s rich literary history.

Enheduanna is the first known author to write in the first person. Scribes had previously written about the king and the gods, but never about themselves or their feelings toward their deities.

The hymns she wrote to Inanna celebrate her individual relationship with the goddess, thereby setting down the earliest surviving verbal account of an individual’s consciousness of her inner life. Historians have also noted that Enheduanna’s work displays a strong sense of a personal relationship with the Divine Feminine:

My Lady, I will proclaim your greatness in all lands and your glory!

Your way and great deeds I will always praise!

I am yours! It will always be so!

May your heart cool off for me

Enehduanna depicts Inanna as both warlike and compassionate. “No one can oppose her murderous battle—who rivals her? No one can look at her fierce fighting, the carnage” (Hymn to Inanna, 49-59). Yet, she also sees the goddess as “weeping daily your heart… know(ing) no relaxation” (Hymn to Inanna, 91-98).

Betty De Shong Meador, who translated Enheduanna hymns in her book, “Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna”clearly stated thatInanna was the only Mesopotamian deity whose character so prominently included contradictions. In her actions, Inanna exhibits both benevolent light and threatening dark. Her violence and destructiveness go beyond the boundaries of tolerable human behaviour.

She carries light and dark to their extremes. Inanna’s immense popularity in antiquity must be related in part to the fact that she could reflect not only the best in human nature, but she could also exhibit what is abhorrent, unpleasant, dirty, sinful, terrifying, abnormal, perverse, obsessive, murderous, mad and violent.

Inanna is a mirror of what Jung called “the abysmal contradictions of human nature.” She shows us our oppositions in sharp relief. She is a divine manifestation of the ultimate conjunction of opposites, displaying for humankind its contradictory nature. And Enheduanna’s hymns were celebrating those contradictions.

Lama Alhassanieh