A little bone in the knee scientists thought was being lost to evolution seems to be making a comeback, say experts.

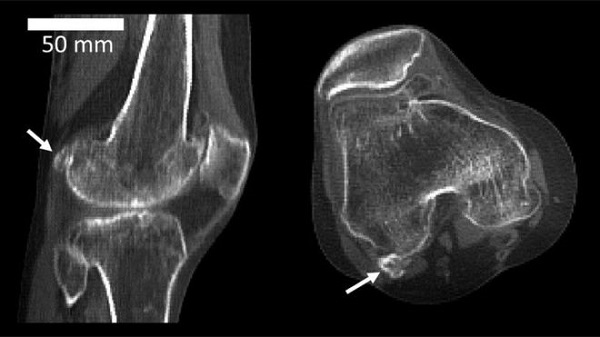

The fabella is found in some people buried in the tendon just behind their knee.

Doctors think it is entirely pointless, and you can happily live without it – many people do.

However, people who have arthritis appear more likely to be in possession of a fabella.

What is it?

In medical terms, the fabella – which means little bean – is a sesamoid bone, meaning it grows in the tendon of a muscle, just like the kneecap or patella.

The doctors have looked back at medical literature on knees over 150 years in 27 countries.

Between 1918 and 2018, reports of the fabella bone’s existence in the knee increased to the extent that it is now thought to be three times as common as 100 years ago.

The scientists’ analysis showed that in 1918, fabellae were present in 11% of the world population, and by 2018, they were present in 39%.

The researchers made their estimations using medical scans and medical journals’ findings from a growing world population.

Doctors said that no-one really knows the answer to that, because it has never been researched.

“The fabella may behave like other sesamoid bones to help reduce friction within tendons, redirecting muscle forces, or, as in the case of the kneecap, increasing the mechanical force of that muscle,” he said.

“Or it could be doing nothing at all.”

Do we need it?

In old world monkeys, the fabella can act as a kneecap, increasing the mechanical advantage of the muscle.

But when the ancestors of great apes and humans evolved, it seemed to disappear.

Now that it has returned, it is just causing us problems, according to experts.

People with osteoarthritis of the knee are twice as likely to have the little bone, but there is no evidence it is actually causing the problem, or how.

The fabella can also get in the way of knee replacement surgery and cause pain and discomfort on its own.

The theory is that it is all to do with nutrition.

The researchers came to the conclusion that better nutrition is making the average human taller and heavier, and this means we have longer shinbones and larger calf muscles.

These changes put the knee under more pressure.

Because sesamoid bones, like the fabella, are known to grow in response to the movements they make and the forces exerted on them, this could explain why the bone is more common than it used to be.

Finding out about this little bone’s resurgence could help doctors treat patients with knee issues.

It could also give them an insight into human evolution over the past century.

But first they want to find out the age, gender and location of people most likely to have a fabella, and if it occurs in one or both knees.

Lara Khouli