Syria will also have a starring role at Josp Fest

Elisabetta Povoledo has been writing about Italy for nearly three decades, and has been working for The New York Times and its affiliates since 1992. She has covered papal conclaves (two), Vatican trials (three), Italian presidents (four), Italian governments (16, in seven legislatures), and Rome’s homeless cat population .She said about Damascus that SOME 16 feet beneath the present-day street level of Damascus, the Syrian capital, just off the Street Called Straight, is a cramped, artificially lighted chapel with roughly cut stones for walls and a few modern pews as furnishings.

The grotto was once part of a home where — 2,000 years ago — Saul of Tarsus is said to have taken shelter after he was blinded by a heavenly light, the incident that converted him to Christianity.

He emerged from that home as the Apostle Paul.

On a recent sultry summer evening, that historical event was very much on the minds of the 20 or so worshipers who watched reverently as a priest stood in front of a modern altar at one end of the small room, arranged the liturgical items he had brought with him, lighted the candles and celebrated Mass. “In the tradition of legions of pilgrims, we find ourselves doing what the early Christians did,” the Rev. Cesare Atuire said during his homily, which addressed the significance of Paul’s message in contemporary society.

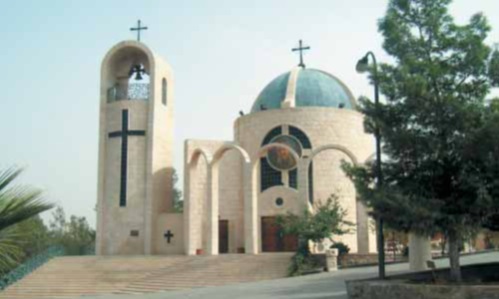

The story of St. Paul in the Chapel of Ananias in Old Damascus.

Since June, similar gatherings have been taking place in churches throughout the world after Pope Benedict XVI inaugurated the jubilee year commemorating the second millennium of Paul’s birth, which historians have placed between A.D. 7 and A. D. 10.

To many present-day pilgrims, however, nothing quite compares with the experience of traveling the road to Damascus. “It’s one thing for Christians to read the Holy Scriptures, quite another to come see where things happened,” said Father Atuire, who is the chief executive officer of the Opera Romana Pellegrinaggi, or ORP, the Vatican-backed travel organization that last year took 300,000 pilgrims to religious shrines around the globe, including its home city, Rome. (This year, it expects that number to hit 400,000.)

Of course, Christians aren’t the only ones showing an interest in religion-based tourism. Participants in the Kumbh Mela, a rotating Hindu festival, have reportedly topped 75 million, and each year, some two million Muslims make a pilgrimage to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia. Nor is Damascus the only place where Christians are heading these days. Lourdes, France, which the Pope visited, draws an average of six million a year (with more than eight million expected this year, officials say, to mark the 150th anniversary of the reported apparition of the Virgin Mary at the grotto), and San Giovanni Rotondo, home to the shrine of the mystic monk Padre Pio, lured eight million to Puglia, Italy, in the last year.

Father Atuire has some thoughts about the surge of believers searching for the roots of their faith. “In times of epochal change, people sense a greater need to find points of reference,” he said while a bus lurched along a Syrian highway to the town of Malula and the Convent of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, another popular pilgrimage site and one of the few places in the world where Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus, is still heard. “But at the same time many are looking for untraditional forms of expression and a pilgrimage allows you to approach a religious experience from a different perspective.”

Pilgrimage destinations, even unconventional ones, are recognizing the potential for growth. Syria, not exactly a top-of-mind vacation destination for Western tourists (the American administration “hasn’t always represented us in a good way,” farmer Syrian tourism minister, Sadallah Agha al-Qala, said in a recent interview), has been making the most of the Pauline year celebrations. “We’re trying to give importance to the jubilee,” said Mr. Agha al-Qala. Both Muslim and Christian Syrians “are proud of the role Damascus played in the history of Christianity.”

Pilgrimage destinations, even unconventional ones, are recognizing the potential for growth. Syria, not exactly a top-of-mind vacation destination for Western tourists (the American administration “hasn’t always represented us in a good way,” farmer Syrian tourism minister, Sadallah Agha al-Qala, said in a recent interview), has been making the most of the Pauline year celebrations. “We’re trying to give importance to the jubilee,” said Mr. Agha al-Qala. Both Muslim and Christian Syrians “are proud of the role Damascus played in the history of Christianity.”

A series of events — concerts, conferences — coordinated by the country’s multiple Christian communities and the government of this most secular of Arab states kicked off the Pauline year, which runs until June 29, 2009. “It was a unique experience,” watching Christian and Muslim leaders celebrate together, “speaking the same language and sharing the same emotions,” Mr. Agha al-Qala said. Another weeklong round of events, coordinated with ORP, is scheduled to end on Jan. 25, the date given for Paul’s conversion.

Father Atuire has played no small part in broadening the scope of ORP, which was founded in 1934 to provide spiritual and logistical support to pilgrimages sponsored by Roman parishes. Until a few years ago, the Vatican organization mostly did business with parishes and groups; now individuals make up 40 percent of its trade. “I’ve been trying to transform ORP into a real Catholic universal organization in terms of geographical and spiritual outreach,” Father Atuire said, “because in times of crisis, this can be of value not only to people who go to church, but for everyone.” Prayer is central to the pilgrimage experience, and spiritual guides accompany each group to celebrate Mass and stimulate discussion. In Syria, where 225 pilgrims have visited on organization tours so far this year, groups might ponder the Crusades while climbing the battlements at the fortified castle known as Crac des Chevaliers, or the tradition of Byzantine icon painting prompted by a visit to the monastery at Seidnaya, which houses a miraculous image of the Virgin reputedly painted by St. Luke.

Then, inside the Umayyad Mosque, the eighth-century structure that houses what is believed to be the head of St. John the Baptist, conversation may turn to Christian-Muslim relations and the shared reverence for this historical figure. ORP has steadily increased its pilgrimage destinations and proposals. “There’s no corner of the globe we don’t touch,” said Father Atuire. This includes Burma, where pilgrims can visit missionary communities.

“It’s the least we can do,” Father Atuire said, laughing. “We are, after all, the church of Rome.”

Adopted by:Haifaa Mafalani