A highly effective tail is needed in order for a sperm to be able to swim, and for a baby to be conceived. By using cryo-electron tomography, researchers have identified a completely new nanostructure inside sperm tails, according to Science Daily.

Human sperms are incredibly important for our reproduction. It would therefore be easy to assume that we have detailed knowledge of their appearance. However, an international team of researchers has now identified a completely new nanostructure inside sperm tails, thanks to the use of cryo-electron tomography.

“Since the cells are depicted frozen in ice, without the addition of chemicals which can obscure the smallest cell structures, even individual proteins inside the cell can be observed” explains Johanna Höög.

The tail affects the ability to swim

A highly effective tail is needed in order for a sperm to be able to swim, and for an egg to be fertilised.

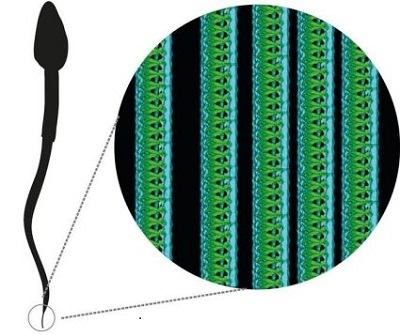

The tail is a highly complex machine that consists of around a thousand different types of building blocks. The most important of these are called tubulins, which form long tubes (microtubules). The tubes are found inside the sperm tail.

Thousands of motorproteins — molecules that can move — are affixed to these tubes. By being fixed to one microtubule and “walking on” the adjacent microtubule, the motorproteins in the sperm tail pull and the tail bends, enabling the sperm to swim.

“It’s actually quite incredible that it can work,” adds Johanna, who led the study. “The movement of thousands of motorproteins has to be coordinated in the minutest of detail in order for the sperm to be able to swim.”

Examining the sperm tail

The research was started in order to see what human sperm tails look like in 3D. This would then provide clues about how sperms work, in the same way that a sketch of an engine helps to explain how it operates.

“When we looked at the first 3D images of the very end section of a sperm tail, we spotted something we had never seen before inside the microtubules: spiral that stretched in from the tip of the sperm and was about a tenth of the length of the tail.”

What the spiral is doing there, what it consists of and whether it is important in order for sperms to swim are questions that the research team will now focus on answering.

“We believe that this spiral may act as a cork inside the microtubules, preventing them from growing and shrinking as they would normally do, and instead allowing the sperm’s energy to be fully focussed on swimming quickly towards the egg,” says Davide Zabeo, the lead PhD student behind the discovery.

N.H.Kh