German intelligence memo shows the threat from the kingdom’s headstrong defence minister, Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

At the end of last year the BND, the German intelligence agency, published a remarkable one-and-a-half-page memo saying that Saudi Arabia had adopted “an impulsive policy of intervention”. It portrayed Saudi defence minister and Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman – the powerful 29-year-old favourite son of the ageing King Salman, who is suffering from dementia – as a political gambler who is destabilising the Arab world through proxy wars in Yemen and Syria.

According to the Independent, spy agencies do not normally hand out such politically explosive documents to the press criticising the leadership of a close and powerful ally such as Saudi Arabia. It is a measure of the concern in the BND that the memo should have been so openly and widely distributed. The agency was swiftly slapped down by the German foreign ministry after official Saudi protests, but the BND’s warning was a sign of growing fears that Saudi Arabia has become an unpredictable wild card. One former minister from the Middle East, who wanted to remain anonymous, said: “In the past the Saudis generally tried to keep their options open and were cautions, even when they were trying to get rid of some government they did not like.”

The BND report made surprisingly little impact outside Germany at the time. This may have been because its publication on 2 December came three weeks after the Paris massacre on 13 November, when governments and media across the world were still absorbed by the threat posed by Islamic State (IS) and how it could best be combatted. In Britain there was the debate on the RAF joining the air war against IS in Syria, and soon after in the US there were the killings by a pro-IS couple in San Bernardino, California.

It was the execution of the Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr and 46 others – mostly Sunni jihadis or dissenters – on 2 January that, for almost the first time, alerted governments to the extent to which Saudi Arabia had become a threat to the status quo. It appears to be deliberately provoking Iran in a bid to take leadership of the Sunni and Arab worlds while at the same time Prince Mohammed bin Salman is buttressing his domestic power by appealing to Sunni sectarian nationalism. What is not in doubt is that Saudi policy has been transformed since King Salman came to the throne last January after the death of King Abdullah.

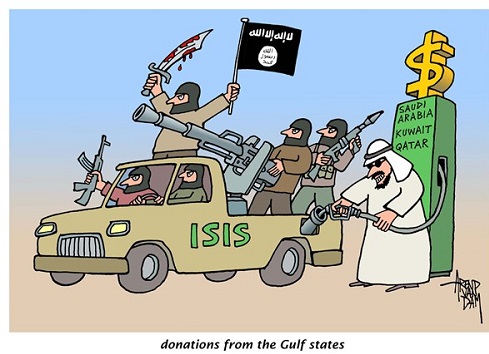

The BND lists the areas in which Saudi Arabia is adopting a more aggressive and warlike policy. In Syria, in early 2015, it supported the creation of The Army of Conquest, primarily made up of the al-Qaeda affiliate the al-Nusra Front and the ideologically similar Ahrar al-Sham, which won a series of victories against the Syrian Army in Idlib province. In Yemen, it began an air war directed against the Houthi movement and the Yemeni army, which shows no sign of ending. Among those who gain are al-Qaeda in the Arabian peninsula, which the US has been fruitlessly trying to weaken for years by drone strikes.

None of these foreign adventures initiated by Prince Mohammed have been successful or are likely to be so, but they have won support for him at home. The BND warned that the concentration of so much power in his hands “harbours a latent risk that in seeking to establish himself in the line of succession in his father’s lifetime, he may overreach”.

The overreaching gets worse by the day. At every stage in the confrontation with Iran over the past week Riyadh has raised the stakes. The attack on the Saudi embassy in Tehran and its consulate in Mashhad might not have been expected but the Saudis did not have to break off diplomatic relations. Then there was the air strike that the Iranians allege damaged their embassy in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen.

None of this was too surprising: Saudi-Iranian relations have been at a particularly low ebb since 400 Iranian pilgrims died in a mass stampede in Mecca last year.

But even in the past few days, there are signs of the Saudi leadership deliberately increasing the political temperature by putting four Iranians on trial, one for espionage and three for terrorism. The four had been in prison in Saudi Arabia since 2013 or 2014 so there was no reason to try them now, other than as an extra pinprick against Iran.

Saudi Arabia has been engaging in something of a counter attack to reassure the world that it is not going to go to war with Iran. Prince Mohammed said in an interview with The Economist: “A war between Saudi Arabia and Iran is the beginning of a major catastrophe in the region, and it will reflect very strongly on the rest of the world. For sure, we will not allow any such thing.”

The interview was presumably meant to be reassuring to the outside world, but instead it gives an impression of naivety and arrogance. There is also a sense that Prince Mohammed is an inexperienced gambler who is likely to double his stake when his bets fail. This is the very opposite of past Saudi rulers, who had always preferred, so to speak, to bet on all the horses.

A main reason for Saudi Arabia acting unilaterally is its disappointment that the US reached an agreement with Iran over Tehran’s nuclear programme. Again this looks naive: close alliance with the US is the prime reason why the Saudi monarchy has survived nationalist and socialist challengers since the 1930s. Aside from the Saudis’ money and close alliance with the US, leaders in the Middle East have always doubted that the Saudi state has much operational capacity. This is true of all the big oil producers, whatever their ideological make-up. Experience shows that vast oil wealth encourages autocracy, whether it is in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Libya or Kuwait, but it also produces states that are weaker than they look, with incapable administrations and dysfunctional armies.

This is the second area in which Prince Mohammed’s interview suggests nothing but trouble for the Saudi royal family. He suggests austerity and market reforms in the Kingdom, but in the context of Middle East autocracies and particularly oil states this breaches an unspoken social contract with the general population. People may not have political liberty, but they get a share in oil revenues through government jobs and subsidised fuel, food, housing and other benefits. Greater privatisation and supposed reliance on the market, with no accountability or fair legal system, means a licence to plunder by those with political power.

This was one of the reasons for the uprising in 2011 against Bashar al-Assad in Syria and Muammar Gaddafi in Libya. So-called reforms that erode an unwieldy but effective patronage machine end up by benefiting only the elite.

Oil states are almost impossible to reform and it is usually unwise to try. Such states should also avoid war if they want to stay in business, because people may not rise up against their rulers but they are certainly not prepared to die for them.

M.A.