In 1964, Italian archaeologists from the University of Rome, La Sapienza under the direction of Paolo Matthiae, began excavating at Tell Mardikh. In 1968, they recovered a statue dedicated to the Goddess Ishtar bearing the name of Ibbit-Lim, a king of Ebla. That identified the city, long known from Egyptian and Akkadian inscriptions. In the next decade the team discovered a palace dating ca. 2500 – 2000 BC. About 2,500 well-preserved cuneiform tablets were discovered in the ruins. About 80% of the tablets are written using the usual Sumerian combination of logograms and phonetic signs, while the others exhibited an innovative, purely phonetic representation using Sumerian cuneiform of a previously unknown Semitic language, which was called Eblaite. Bilingual Sumerian/Eblaite vocabulary lists were found among the tablets, allowing them to be translated.

It now appears that the building housing the tablets was not the palace library, which may yet be uncovered, but an archive of provisions and tribute, law cases and diplomatic and trade contacts, and a scriptorium where apprentices copied texts. The larger tablets had originally been stored on shelves, but had fallen onto the floor when the palace was destroyed. The location where tablets were discovered where they had fallen allowed the excavators to reconstruct their original position on the shelves. It soon appeared that they were originally shelved according to subject.

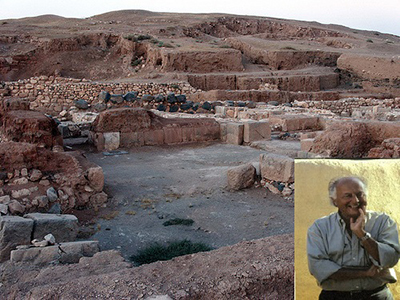

Ebla in the third millennium BC

It has been suggested that a possible explanation of the word “Ebla” is “white rock”, referring to the limestone outcrop on which the city was built. Although the site shows signs of continuous occupation from before 3000 BC, its power grew and reached its peak in the second half of the following millennium. Ebla’s first apex was between ca. 2400 and 2240 BC. Its name is mentioned in texts from Akkad from ca. 2300 BC.

Most of the Ebla palace tablets, which date back to that period, are about economic matters; they provide a good look into the everyday life of the inhabitants, as well as many important insights into the cultural, economic, and political life in northern Mesopotamia around the middle of the third millennium B.C. The texts are accounts of the state revenues, but they also include royal letters, Sumerian-Eblaite dictionaries, school texts and diplomatic documents, like treaties between Ebla and other towns of the region.

The fifth and last king of Ebla during this period was Ebrium’s son, Ibbi-Zikir, the first to succeed in a dynastic line, thus breaking with the established Eblaite custom of electing its ruler for a fixed term of office, lasting seven years. This absolutism may have contributed to the unrest that was ultimately instrumental in the city’s decline. Meantime, however, the reign of Ibbi-Zikir was considered a time of inordinate prosperity, in part because the king was given to frequent travel abroad. It was recorded both in Ebla and Aleppo that he concluded specific treaties with neighboring Armi, as Aleppo was called at the time.

Economy

At that time, Ebla was a major commercial center. Its major commercial rival was Mari, with whom it fought a lengthy war estimated as lasting 80–100 years. The tablets reveal that the city’s inhabitants owned about 200,000 head of mixed cattle (sheep, goats, and cows). The city’s main articles of trade were probably timber from the nearby mountains (and perhaps from Lebanon), and textiles (mentioned in Sumerian texts from the city-state of Lagash). Most of its trade seems to have been directed (by river-boat) towards Mesopotamia (chiefly Kish). The main palace at Ebla was also found to contain “antiques” dating from Ancient Egypt with the names of pharaohs Khafra and Pepi I. Handicrafts may also have been a major export. Exquisite artifacts have been recovered from the ruins, including wood furniture inlaid with mother-of-pearl and composite statues created from different colored stones. The artistic style at Ebla may have influenced the quality work of the Akkadian empire.

L. Nasser