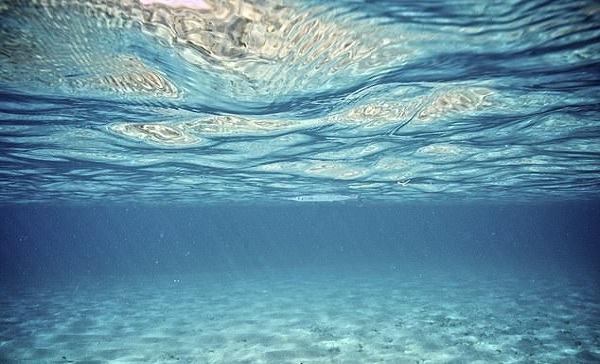

The chalky white seafloor, made up largely of calcite formed from the remains of marine organisms, is rapidly dissolving as a result of human activity, scientists warn.

This mineral plays a key role in preventing the ocean from becoming too acidic, by neutralizing carbon dioxide in the water, according to Daily Mail.

In several regions, the influx of carbon dioxide is much more than the naturally occurring calcite can handle, causing it instead to dissolve and turn the ocean floor into a murky brown.

According to a new study from McGill University the phenomenon occurring in these areas is likely just a glimpse at what will soon be a much bigger issue.

‘Because it takes decades or even centuries for CO2 to drop down to the bottom of the ocean, almost all the CO2 created through human activity is still at the surface,’ said lead author Olivier Sulpis.

‘But in the future, it will invade the deep-ocean, spread above the ocean floor and cause even moer calcite particles at the seafloor to dissolve.

‘The rate at which CO2 is currently being emitted into the atmosphere is exceptionally high in Earth’s history, faster than at any period since at least the extinction of the dinosaurs.

‘And at a much faster rate than the natural mechanisms in the ocean can deal with, so it raises worries about the levels of ocean acidification in future.’

The researchers recreated the conditions of the deep-sea in the lab, replicating the bottom currents, seawater temperature, chemistry, and sediment compositions.

By comparing the dissolution rates from pre-industrial and current times, they found human activity in the last several decades has dramatically sped up the process.

‘Just as climate change isn’t just about polar bears, ocean acidification isn’t just about coral reefs,’ said former postdoctoral fellow, David Trossman, who is now a research associate at the University of Texas-Austin.

‘Our study shows that the effects of human activities have become evident all the way down to the seafloor in many regions, and the resulting increased acidification in these regions may impact our ability to understand Earth’s climate history.’

The researchers now plan to investigate how this effect will evolve in the years to come.

‘This study shows that human activities are dissolving the geological record at the bottom of the ocean,’ says University of Michigan physical oceanographer Brian Arbic.

‘This is important because the geological record provides evidence for natural and anthropogenic changes.’

N.H.Kh