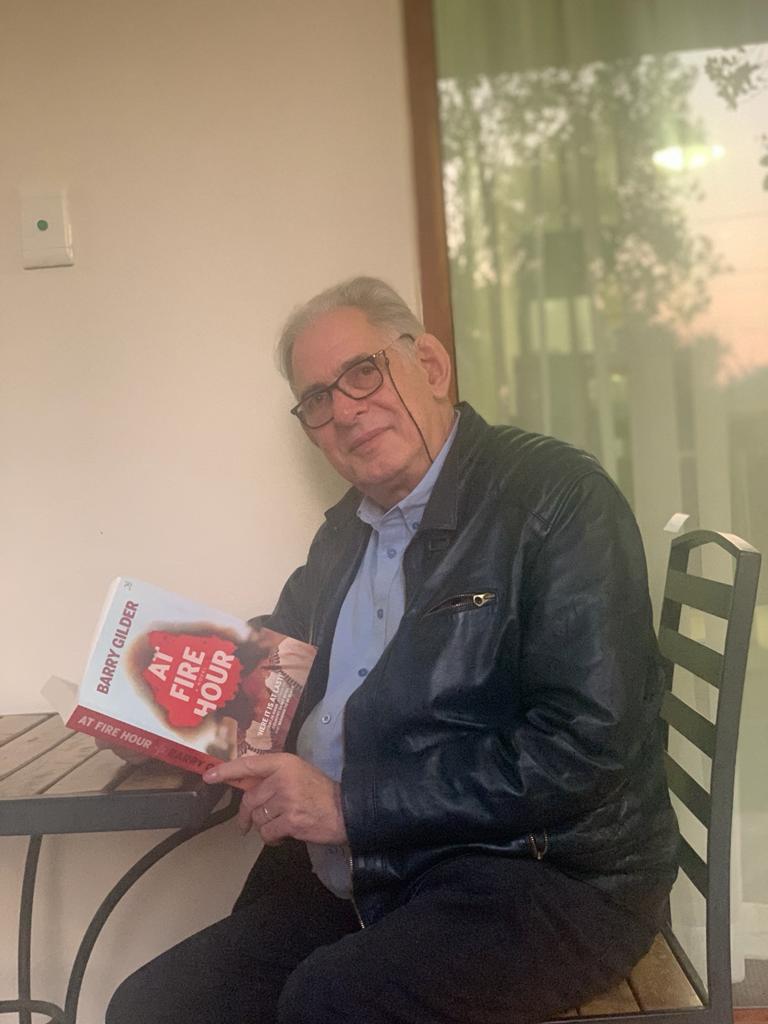

“The writer is as important as the fighter-for the writer presents in the form he chooses what the fighter has done “ These were the words of South Africa’s Ambassador in Syria Barry Gilder to Syriatimes in a special interview about his latest fiction publication “At Fire Hour”, which was launched in SouthAfrica on Wednesday 13th of September 2023When asked about how he chose this unexpected or “different “title for his book, he said“The title – ‘At Fire Hour’ – comes from a segment of a poem by the South African poet Arthur Nortje who died in exile in 1971. The relevant lines of the poem are:and let no amnesiaattack at fire hour:for some of us must storm the castlessome define the happening. One interpretation of these lines is that, in a revolutionary struggle, the role of the writer or artist is to make art about the struggle while others do the fighting. The novel was written in part fulfilment of a PhD in creative writing, which also required me to submit a scholarly essay. Both the novel and the essay explore those South African writers and artists who did both – stormed the castles and defined the happening.The main character in the novel is just such a writer and one of the key themes of the book is the tension between his art and his revolutionary activism.To be honest, my motivation for writing this novel lay largely in my own life experience. My political life started off as a cultural activist. In my early years I was a singer-songwriter, composing and singing songs about apartheid and our struggle against it. Like the main character in the novel, I went into exile in 1976, underwent military training with the African National Congress’s armed wing, did further training in the then Soviet Union, and worked in the ANC underground in Botswana. But, in my case, my artistic work went into abeyance the deeper I became involved in the ANC underground intelligence and military work. It is only after my stint in the post-apartheid government, that my creative side could emerge again, initially with the writing of my non-fiction book.By the way, the Arab Writers Union recently offered to translate the new novel into Arabic, so I hope both the English and Arabic versions will be available in Syria soon and your readers will rush to get a copy. It will also be available shortly as an e-book on Amazon.” (Use your VPN!)Syriatimes wanted to know whether “At Hour Fire” was based on facts“In the Acknowledgements at the end of the novel, I say the following:In the novel, there are a number of characters who are based on real people – some passed on, some still alive. These characters are portrayed purely fictionally. With few exceptions, none of the things they say or do in the novel are things they said or did in real life and should not be ascribed to them. The novel includes a number of real events – conferences that took place in Amsterdam, Gaborone and Vic Falls – and extracts in the novel from papers presented at these conferences by these ‘real’ characters, as well as the conference resolutions, are real.Aspects of the novel are rooted in the realities of the South African anti-apartheid struggle, the armed struggle, the international solidarity mobilization, and the struggle of artists to contribute their art and themselves to that struggle. So some ‘real’ people who were involved in the struggle appear fictionally in the novel, but the main character Bheki, and his wife Pumla, are totally fictional – fictional characters living in a real world.I came across a most apt quote recently, that is ascribed to E. L. Doctorow, an American novelist best known for his works of historical fiction: ‘The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.’”

One interpretation of these lines is that, in a revolutionary struggle, the role of the writer or artist is to make art about the struggle while others do the fighting. The novel was written in part fulfilment of a PhD in creative writing, which also required me to submit a scholarly essay. Both the novel and the essay explore those South African writers and artists who did both – stormed the castles and defined the happening.The main character in the novel is just such a writer and one of the key themes of the book is the tension between his art and his revolutionary activism.To be honest, my motivation for writing this novel lay largely in my own life experience. My political life started off as a cultural activist. In my early years I was a singer-songwriter, composing and singing songs about apartheid and our struggle against it. Like the main character in the novel, I went into exile in 1976, underwent military training with the African National Congress’s armed wing, did further training in the then Soviet Union, and worked in the ANC underground in Botswana. But, in my case, my artistic work went into abeyance the deeper I became involved in the ANC underground intelligence and military work. It is only after my stint in the post-apartheid government, that my creative side could emerge again, initially with the writing of my non-fiction book.By the way, the Arab Writers Union recently offered to translate the new novel into Arabic, so I hope both the English and Arabic versions will be available in Syria soon and your readers will rush to get a copy. It will also be available shortly as an e-book on Amazon.” (Use your VPN!)Syriatimes wanted to know whether “At Hour Fire” was based on facts“In the Acknowledgements at the end of the novel, I say the following:In the novel, there are a number of characters who are based on real people – some passed on, some still alive. These characters are portrayed purely fictionally. With few exceptions, none of the things they say or do in the novel are things they said or did in real life and should not be ascribed to them. The novel includes a number of real events – conferences that took place in Amsterdam, Gaborone and Vic Falls – and extracts in the novel from papers presented at these conferences by these ‘real’ characters, as well as the conference resolutions, are real.Aspects of the novel are rooted in the realities of the South African anti-apartheid struggle, the armed struggle, the international solidarity mobilization, and the struggle of artists to contribute their art and themselves to that struggle. So some ‘real’ people who were involved in the struggle appear fictionally in the novel, but the main character Bheki, and his wife Pumla, are totally fictional – fictional characters living in a real world.I came across a most apt quote recently, that is ascribed to E. L. Doctorow, an American novelist best known for his works of historical fiction: ‘The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.’” Ambassador Gilder goes on to say that this book was not censored ,“By whom? No. It did go through a rigorous editorial process through my PhD supervisor, and the editor assigned by the publisher. But that was purely artistic, literary editing.Interestingly, my first book Songs and Secrets (which has recently been translated into Arabic), is more or less a memoir and includes detailed anecdotes about my time in democratic South Africa’s intelligence services. I was required by law to submit it to the intelligence service for scrutiny before publication. To my surprise (and pleasure) the manuscript came back without any cuts. They only corrected the spelling of some of the names in the book.”Fiction comes easier to Ambassador Gilder.“I would say fiction is closer to my creative spirit, although my non-fiction book would be classified as creative non-fiction. In fiction, my characters tend to take on a life of their own and, for much of the time spent working on a novel, I live in their world. And, sometimes, when something bad happens to one of my characters, I find tears welling up in my eyes.But, because my fiction – so far – is based on the real world and real history, it often requires a similar amount of research and efforts towards accuracy that non-fiction requires.”The last question was about whether Ambassador Gilder would ever consider writing a book about Syria and his perception of what happened

Ambassador Gilder goes on to say that this book was not censored ,“By whom? No. It did go through a rigorous editorial process through my PhD supervisor, and the editor assigned by the publisher. But that was purely artistic, literary editing.Interestingly, my first book Songs and Secrets (which has recently been translated into Arabic), is more or less a memoir and includes detailed anecdotes about my time in democratic South Africa’s intelligence services. I was required by law to submit it to the intelligence service for scrutiny before publication. To my surprise (and pleasure) the manuscript came back without any cuts. They only corrected the spelling of some of the names in the book.”Fiction comes easier to Ambassador Gilder.“I would say fiction is closer to my creative spirit, although my non-fiction book would be classified as creative non-fiction. In fiction, my characters tend to take on a life of their own and, for much of the time spent working on a novel, I live in their world. And, sometimes, when something bad happens to one of my characters, I find tears welling up in my eyes.But, because my fiction – so far – is based on the real world and real history, it often requires a similar amount of research and efforts towards accuracy that non-fiction requires.”The last question was about whether Ambassador Gilder would ever consider writing a book about Syria and his perception of what happened “I don’t know, to be honest. After this novel, I need some time for the next one to germinate. But in this novel, Syria does make a brief appearance – Maxim, the son of Beki and Pumla, in later life (in 2020 to be exact), is working as a First Secretary in the South African embassy in Damascus, and his mother back in South Africa is anxious about the frequent Israeli missile attacks on Damascus.”

“I don’t know, to be honest. After this novel, I need some time for the next one to germinate. But in this novel, Syria does make a brief appearance – Maxim, the son of Beki and Pumla, in later life (in 2020 to be exact), is working as a First Secretary in the South African embassy in Damascus, and his mother back in South Africa is anxious about the frequent Israeli missile attacks on Damascus.”

Editor In Chief

Reem Haddad